INTERNACIONAL

Brazil’s Supreme Court decriminalizes possession of marijuana for personal use

Brazil’s Supreme Court on Tuesday voted to decriminalize possession of marijuana for personal use, making the nation one of Latin America’s last to do so, in a move that could reduce its massive prison population.

With final votes cast on Tuesday, a majority of the justices on the 11-person court have voted in favor of decriminalization since deliberations began in 2015.

BRAZIL TO RULE WHETHER BUSINESSES CAN PLANT CANNABIS, POTENTIALLY OPENING PASSAGE TO LEGAL CULTIVATION

The justices must still determine the maximum quantity of marijuana that would be characterized as being for personal use and when the ruling will enter into effect. That is expected to finish as early as Wednesday.

The Brazilian Supreme Court meets during the session regarding Brazil’s former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s corruption conviction, in Brasília, Brazil, April 4, 2018. The Supreme Court decriminalized possession of marijuana for personal use on Tuesday, June 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

All the justices who have voted in favor said decriminalization should be restricted to possession of marijuana in amounts suitable for personal use. Selling drugs will remain illegal.

In 2006, Brazil’s Congress approved a law that sought to punish individuals caught carrying small amounts of drugs, including marijuana, with alternative penalties such as community service. Experts say the law was too vague and didn’t establish a specific quantity to help law enforcement and judges differentiate personal use from drug trafficking.

Police continued to arrest people carrying small quantities of drugs on trafficking charges and Brazil’s prison population continued to swell.

«The majority of pre-trial detainees and those convicted of drug trafficking in Brazil are first-time offenders, who carried small amounts of illicit substance with them, caught in routine police operations, unarmed and with no evidence of any relationship with organized crime,» said Ilona Szabó, president of Igarapé Institute, a think tank focusing on public security.

Congress has responded to the top court’s ongoing deliberations by separately advancing a proposal to tighten drug legislation, which would complicate the legal picture surrounding marijuana possession.

In April, the Senate approved a constitutional amendment criminalizing possession of any quantity of illicit substance. The lower house’s constitutional committee approved the proposal on June 12, and it will need to pass through at least one other committee before going to a floor vote.

If lawmakers pass such a measure, the legislation would take precedence over the top court’s ruling but still could be challenged on constitutional grounds.

Speaking to reporters in capital Brasilia, the Senate’s president, Rodrigo Pacheco, said it isn’t the Supreme Court’s place to issue a decision on the matter.

«There is an appropriate path for this discussion to move forward and that is the legislative process,» he said. «It is something that, obviously, arouses broad discussion and it is a subject of preoccupation for Congress.»

Last year, a Brazilian court authorized some patients to grow cannabis for medical treatment after the health regulator in 2019 approved guidelines for the sale of medicinal products derived from cannabis. But Brazil is one of a few countries in Latin America that hasn’t decriminalized the possession of small quantities of drugs for personal consumption.

The Supreme Court’s ruling has long been sought by activists and legal scholars in a country where the prison population has become the third largest in the world. Critics of current legislation say users caught with even small amounts of drugs are regularly convicted on trafficking charges and locked up in overcrowded jails, where they are forced to join prison gangs.

«Today, trafficking is the main vector for imprisonment in Brazil,» said Cristiano Maronna, director of JUSTA, a civil society group focusing on the justice system.

Brazil ranks behind U.S. and China in countries with the highest prison populations, according to the World Prison Brief, a database tracking such figures.

Some 852,000 individuals were deprived of liberty in Brazil as of December 2023, according to official data. Of those, nearly 25% were arrested for possession of drugs or trafficking. Brazilian jails are overcrowded, and Black citizens are disproportionately represented, accounting for more than two-thirds of the prison population.

A recent study by Insper, a Brazilian research and education institute, determined that Black individuals found by police with drugs were slightly more likely to be indicted as traffickers than white people. The authors analyzed over 3.5 million records from Sao Paulo’s public security secretariat from 2010 to 2020.

«An advance in drug policy in Brazil! This is an issue of public health, not security and incarceration,» leftist lawmaker Chico Alencar wrote on X after the ruling.

By contrast, Gustavo Scandelari, a specialist on Brazil’s penal code at law firm Dotti Advogados, said he doesn’t foresee the ruling bringing about a significant shift from the status quo, even after the top court establishes a maximum quantity of marijuana for personal use. Scandelari argued that the amount will remain one determinant of whether authorities consider a person a dealer or a user, but not the only one.

Some Brazilians, like 47-year-old Rio de Janeiro resident Alexandro Trindade, have managed to be upset with both the Supreme Court decriminalizing marijuana and Congress pushing to keep it illegal.

«The Supreme Court is not the right place (for such decision). This should be submitted to a plebiscite for the people to decide,» Trindade said. «Both the Supreme Court and Congress have been very opposed to society in this.»

As in other countries in the region, like Argentina, Colombia and Mexico, medicinal use of cannabis in Brazil is allowed, though in a highly restricted manner.

Uruguay has fully legalized the use of marijuana, and in some U.S. states recreational use for adults is legal. In Colombia, possession has been decriminalized for a decade, but a law to regulate the recreational use of marijuana so that it can be sold legally failed to pass in the Senate in August. Colombians can carry small amounts of marijuana, but selling it for recreational purposes is not legal.

The same goes for Ecuador and Peru. Both distribution and possession remain illegal in Venezuela.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Argentina’s Supreme Court ruled in 2009 it was unconstitutional to penalize an adult for consuming marijuana if it didn’t harm others. But the law has not been changed and users are still arrested, although most cases are thrown out by judges.

Uruguay became the first country to legalize marijuana for recreational use in 2013 although it was only implemented in 2017. Uruguay’s whole industry, from production to distribution, is under state control and registered users can buy up to 40 grams of marijuana per month through pharmacies.

INTERNACIONAL

Saeed Jalili, a hard-line former negotiator known as a ‘true believer,’ seeks Iran’s presidency

Hard-line Iranian presidential candidate Saeed Jalili may have been Tehran’s top nuclear negotiator for years, but he won no plaudits from Western diplomats sitting across the table as he repeatedly lectured them on everything while offering nothing.

«As the weaving of Iranian carpets progresses in millimeter, precise, delicate and durable manner, God willing, this diplomatic process will also proceed in the same way,» Jalili said then.

IRAN VOWS TO BACK HEZBOLLAH IN FIGHT WITH ISRAEL AS IRGC GENERAL RENEWS THREAT OF IMMINENT MISSILE STRIKE

Those hours of lecturing in 2008 stalled talks as hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei advanced the country’s nuclear program. That put pressure on the West that eventually eased with Iran’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, which lifted sanctions on the Islamic Republic.

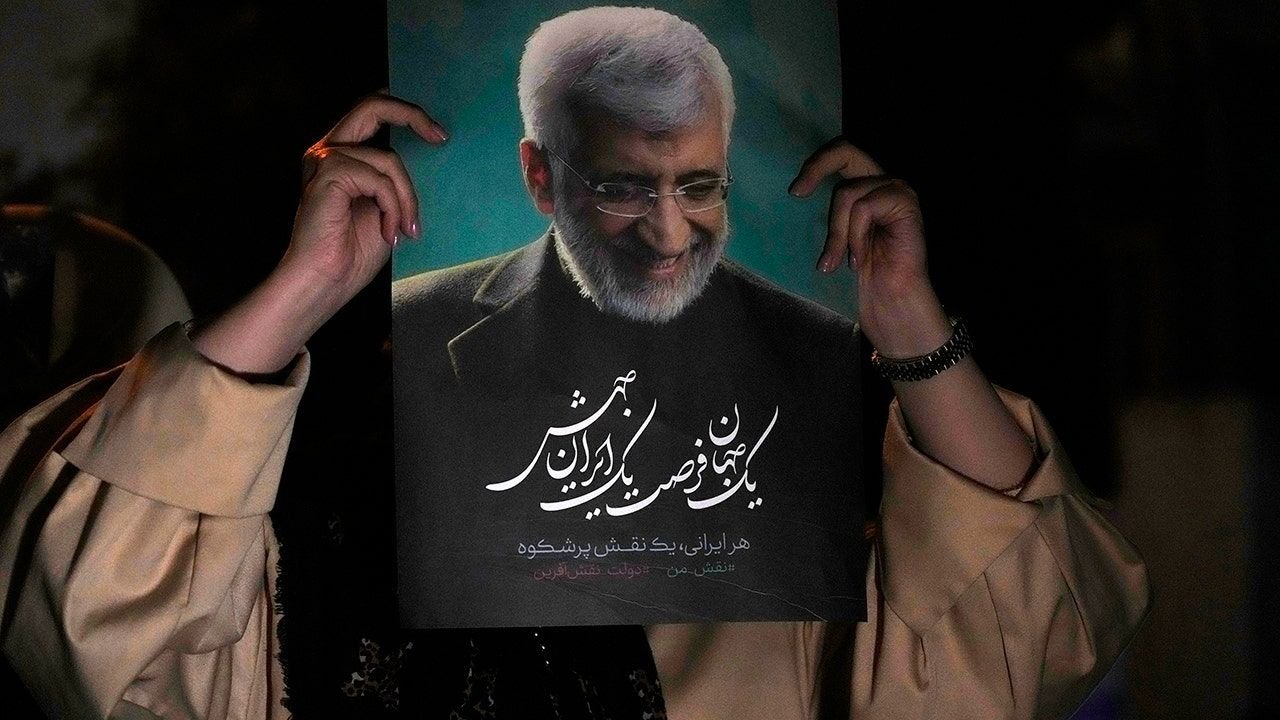

A supporter of Iranian presidential candidate Saeed Jalili holds up a poster of Jalili during his campaign stop in Tehran, Iran, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi)

Now Jalili, 58, stands on the precipice of being elected as Iran’s next president as he faces a runoff election Friday against the little-known reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon. With Iran’s nuclear program enriching uranium at levels near-weapons grade, a win by Jalili may again see already-stalled negotiations freeze.

Meanwhile, Jalili’s own hard-line vision for Iran — derided by opponents as being in the style of the Taliban — potentially risks inflaming a public still angry after the bloody security force crackdown that followed the demonstrations over the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini. She died in police custody after she was detained over allegedly improperly wearing the mandatory headscarf, or hijab.

Jalili, known for his shock of white hair and beard, is known as the «Living Martyr» after losing his right leg in combat at the age of 21 during the 1980s Iran-Iraq war. He was born Sept. 6, 1965, in the Shiite holy city of Mashhad, his Kurdish father a French teacher and a school principal and his mother an Azeri.

Jalili worked as a university professor with a doctorate before joining Iran’s Foreign Ministry, working his way up to a top position before joining Iran’s Supreme National Security Council and becoming the country’s top nuclear negotiator under Ahmadinejad from 2007 to 2013.

He made an impression immediately on his Western counterparts, with then-negotiator, now-CIA director William Burns calling him «a true believer in the Iranian Revolution.»

«He could be stupefyingly opaque when he wanted to avoid straight answers, and this was certainly one of those occasions,» Burns recalled in one meeting. «He mentioned at one point that he still lectured part-time at Tehran University. I did not envy his students.»

An anonymous French diplomat quoted at the time referred to one round of Jalili’s negotiations as a «disaster.»

Another European Union diplomat offered a similar assessment in a 2008 U.S. diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks.

«An EU official who attended Jalili’s private and public meetings that day was struck by his seeming inability or unwillingness to deviate from the same presentation or provide nuance, calling him ‘a true product of the Iranian Revolution,'» the cable said, not naming the diplomat.

Jalili later would be replaced after he came in a distant third in Iran’s 2013 presidential election to the relatively moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani, himself a former nuclear negotiator. Rouhani’s administration would secure the 2015 nuclear deal, which saw Iran drastically reduce the size and purity of its stockpile of enriched uranium in exchange for the lifting of economic sanctions.

Jalili strongly opposed the deal and formed what he described as a «shadow government» during the Rouhani years to try to undercut his efforts. Jalili also was endorsed in his 2013 run by the late hard-line Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, who once wrote that Iran should not deprive itself of the right to produce «special weapons» — a veiled reference to nuclear weapons.

Iran long has insisted its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes.

However, U.N. inspectors and Western nations say Iran had an organized military nuclear program until 2003. In recent months, Iranian officials have increasingly made threats about Iran’s ability to build a bomb if it wanted as it enriches uranium to 60% purity, a short, technical step to weapons-grade levels of 90%.

Meanwhile, advocates for Pezeshkian have described Jalili as potentially bringing hard-line policies akin to the Taliban if he’s elected, something Jalili acknowledged in passing.

«Before the election results were even announced, we called 10 million or 9 million people Taliban?» Jalili said at a recent debate, referring to reformists’ criticism of his policies. «Does this help?»

Jalili hasn’t offered any real comment on how he’d handle the ongoing dispute over the hijab in Iranian society. But those in Jalili’s campaign have been much more direct — calling for stricter punishment against those refusing to wear the mandatory headscarf. One once referred to uncovered women as being worse than a «whore.» Yet during his campaign, Jalili has been vague about how he’d enforce the law and has even posed for a selfie with a woman with a loose hijab, a moment captured in a news photo.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Jalili also has been endorsed by another fundamentalist ayatollah, Mohammad Mehdi Mirbagheri, who belongs to the Front of Islamic Revolution Stability, the far-right edge of hard-liners in the nation. The group, which backs Jalili, was behind a bill passed by Iran’s parliament that could impose 10-year prison sentences for hijab violations. It has yet to be approved by the country’s Guardian Council, a panel of clerics and jurists ultimately overseen by Khamenei.

«They want blocking and closures in everything, no matter the field,» political analyst Mehrdad Khadir told The Associated Press. «It’s the same when it comes to the issue of women, internet or any other issue.»

-

POLITICA3 días ago

Cristina Kirchner reapareció y criticó al Gobierno: “El superávit fiscal es cada vez más trucho”

-

POLITICA2 días ago

El PRO publicó un duro informe y cuestionó el rumbo del Gobierno: “Hay más interrogantes que certezas”

-

POLITICA3 días ago

Los mercados castigan a Milei, la ayuda de los «dinosaurios» y una anomalía del Senado

-

ECONOMIA3 días ago

Nuevo aumento de naftas y gasoil a partir del 1 de julio

-

POLITICA1 día ago

La reacción del Gobierno ante la suba del dólar blue: “No vamos a devaluar ni a corrernos del plan de Caputo”

-

POLITICA22 horas ago

Tras la tensión diplomática, Lula quiere eliminar el acuerdo automotriz con Argentina